A Triple Tribute: Helen Frankenthaler, Lee Krasner, and Joan Mitchell

At the edge of the spotlight, not fully illuminated, are women abstract expressionists who significantly enhance our understanding of American art in the mid-20th century.

A few of the dozen women featured in the Denver Art Museum’s Women of Abstract Expressionism exhibition are names we may be slightly familiar with: Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011), Lee Krasner (1908–1984), and Joan Mitchell (1925–1992). Their contributions to this vibrant American art movement are important. Each woman had an incredible life and career, covered briefly here, but with a multitude of links for those interested in digging more deeply. We’ll begin this week with Helen Frankenthaler and turn to the other two in the weeks to come.

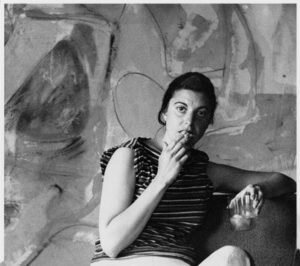

Helen Frankenthaler was a major contributor to the history of postwar American painting. Born in 1928 and raised in New York City, she received her earliest art instruction from Mexican artist Rufino Tamayo. In 1949 she graduated from Bennington College and then moved on to study with Hans Hofmann the next year and began exhibiting her work. Her first solo exhibit was in 1951 at New York’s Tibor de Nagy Gallery and that same year she was included in the 9th St. Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture. For five years she and influential art critic Clement Greenberg were lovers. His recognition of her originality played a role in bringing her imaginative work to international attention.

Although Frankenthaler was well acquainted with the older abstract expressionists (abex), who were early influences on her own art, she was much younger and would go on to become one of the most prominent artists in the second generation of abex artists. Jackson Pollock, for example, inspired her to develop her own technique of “stain painting,” pouring thinned paint onto unstretched, unsized cotton canvas to develop her artistic visions. Her personal interpretation of this method can be seen in Mountains and Sea (1952), which is considered her breakthrough work (see image to the right, and note the grand scale). Her process, in turn, influenced later waves of color-field artists. In 1958 she married artist Robert Motherwell (they divorced in 1971), and for a while they were known about town as “the golden couple.”

Frankenthaler was a life-long experimenter and innovator and worked in a number of mediums, including ceramics, welded steel sculptures, and set designs, but the mediums that most attracted her in addition to painting, were printmaking and woodcuts. She became fascinated with the 17th-century Japanese Ukiyo-e woodcuts and in the 1970s studied with Japanese artisan woodcarver Yasuyuki shibata. Her woodcuts in this style became some of her most sought-after editions, as exemplified by her series Book of Clouds (2007).

Clearly, Helen Frankenthaler was one of the most multi-talented artists of her generation. Observer critic Nigel Gosling’s description of Frankenthaler’s art, in a review of an exhibition in May 1964 at the Kasmin gallery in London, is apt:

If any artist can give us aid and comfort,” he wrote, “Helen Frankenthaler can with her great splashes of soft colour on huge square canvases. They are big but not bold, abstract but not empty or clinical, free but orderly, lively but intensely relaxed and peaceful . . . They are vaguely feminine in the way water is feminine—dissolving and instinctive, and on an enveloping scale.

Frankenthaler exhibited her work for over six decades. She was one of a handful of artists representing the United States at the 33rd Venice Biennale (1966) and her work has been the subject of several retrospective exhibitions, including a 1989 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. In 2001, she was awarded the National Medal of Arts.

There is no doubt that Helen Frankenthaler was an important contributor to both American abstract expressionism and the color-field school that evolved within it. She was deeply embedded in the New York art culture of her times and had the strength to rise above what others were doing and forge her own unique path.

For more: See http://www.frankenthalerfoundation.org/. For a biography: Helen Frankenthaler: Painting History, Writing Painting by Alison Rowley (2008) – I have not yet read this, but the hardcover is a collector’s item so extremely expensive but probably available through some libraries. There is a wonderful interview/oral history with Frankenthaler in the Smithsonian archives of American art. # # #

Check out the trailer for the Denver Art Museum show of Women of Abstract Expressionism. Wonderful clips of many of the artists talking about their work. Accompanying the Denver Art Museum exhibition is a stunning catalog, Women of Abstract Expressionism, filled with insightful essays and images. Social media request: I hope you’ll help spread the word about this series on the Divine Dozen. If you do, please use the hashtag #womenofabex