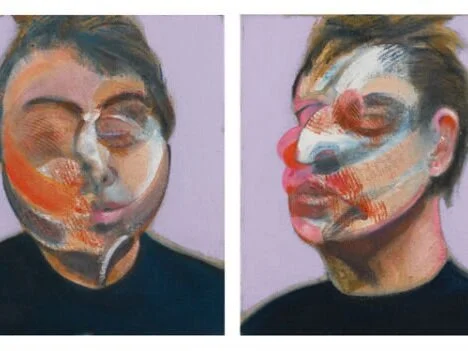

Abstract Art: When Is A Portrait Not a Likeness?

When you walk into an art gallery, what type of art is most likely to first catch your eye? The seascape, mountain scene, or wildlife? Paintings or sculptures of people realistically portrayed? Or are you drawn to a bold design filled with line and form, but no recognizable subject?

Many art lovers find pleasure in art that reminds them of their own connections to the land, to amazing replications of wild animals or scenes of human activity that suggest a story in progress. These types of works are often easier to access, to feel an emotional response to, because our brains can categorize them and open a channel within us about what they mean. We connect through who we are, influenced by all of our personal experiences. And we evaluate these works according to how well we think the artist has represented his or her subject.

But does an artwork have to have a “meaning”? Can it simply offer an undirected experience?

City with Animals, Oil on canvas, 1919, Max Ernst

Things changed in the art world around the second decade of the 20th century, with the rise of surrealism (e.g., Max Ernst [1891-1976], Andre Breton [1896-1966]), cubism (e.g. Pablo Picasso [1881-1973], Georges Braque [1882-1963]), and, after WWII, American abstract expressionism. No longer was the human figure mythically idealized, the landscape romantically rendered. Of course, artists continued working in representative styles, but the buzz of the day now ranged from Wassily Kandinski’s (1866-1944) first purely abstract works to surrealism’s fantastical compositions and Picasso’s sometimes bizarre and fractured subjects. Not everyone felt comfortable with the newer styles, but everyone flocked to see them, and artists felt increasingly inspired to push boundaries, no longer confined to recognizable subject matter alone.

The abstract expressionism movement began in the 1940s after WWII. Although its center was New York City, there were notable examples of the movement’s influence produced by artists in the Pacific Northwest (e.g., Mark Tobey [1890-1976] and the San Francisco Bay Area (e.g., Sonia Gechtoff [1926-2018] ). Among those artists most widely known in the movement are Jackson Pollock, Willem DeKooning, Robert Motherwell, and a handful of others. Only recently has the spotlight for the period shifted to reveal the talented women active in that period.

Through the years, my own taste in art has waxed and waned, shape-shifted. I’ve had enthusiasms that later seemed not nearly as compelling. I’ve had the good fortune to make my living writing about art, artists, and art history, and I am always reading about it because there is never an end to what we can learn. It all influences how I appreciate something that reaches beyond realistic representation. My first love continues to be beautifully crafted portrayals of people, but I’ve also gained a deep regard for still life and abstraction by artists who understand color theory and design. They know how to go beyond what my eyes tell me and ignite an emotional, unconscious switch in my brain, drawing me back again and again without knowing why.

I’ve been reading award-winning furniture maker Peter Korn’s book, Why We Make Things and Why It Matters: The Education of a Craftsman (2013). Some of it is dry and dense, but there are jewels to be found among its pages. His description of abstract expressionism is the best I’ve found:

The artist divines truth entirely from within as each brushstroke, mark, drip, or splatter registers his internal response to its predecessors on the canvas. The resulting abstract image [is] neither more nor less than a self-referential record of one person’s inner creative exploration, a portrait of his intuition.

“A portrait of his intuition”—this makes perfect sense to me. All painters make a thousand decisions, step by step, as they move through their process from inspiration to the final sweep of their brush or palette knife, but those working representationally make those decision by responding to something in front of them, to reference materials, or to a concrete vision. The artist working abstractly makes each of those decision by “feel”—by his or her gut response to the present moment. The best of these combine intuition and deliberation. The success of their work of art depends entirely on how richly developed their inner sense of color and design are.

Personally, I still don’t get anything from the all-black canvas no matter how many critics tell me it’s about the materials, the characteristics of the paint or canvas, and so on. My response to it is, “So what?” not “Wow.” But next time you go to an exhibition, glance around the room to see if anything nonrepresentational jumps out at you, keeps you coming back. Take a few minutes to note how it communicates with color, line, and form. See if marks, drips, patterns, or a sense of movement make it interesting. You may never become an abstract groupie but, once in a while, visual treasure awaits you! As with ordinary conversation, it is sometimes a facial expression rather than words themselves that tell the story.

For more about abstract art and its influential painters, go here.