Ep. 8: Breaking with the Past, 1936

In 1936, 29-year-old Annette Pepper fled her marriage to staid New York attorney Sidney Pepper to join the love of her life, Louis Stephens, in Mexico City.

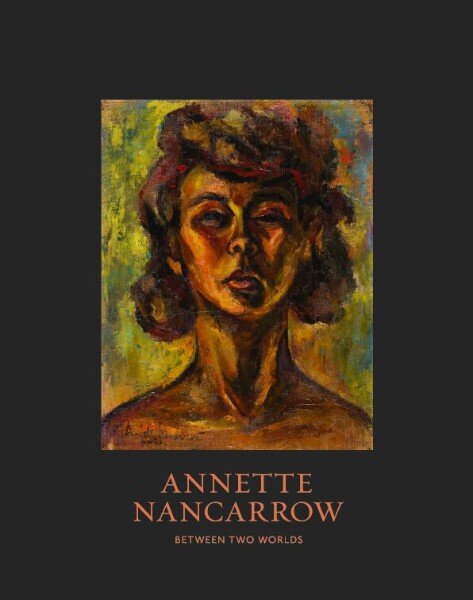

Cover of book, Foreword by Rosemary Carstens, created to complement a 2014 Taubman Museum. VA, exhibition of Annette’s artwork

Annette told Sidney she was taking two-year-old Cherry to Florida for a vacation in warmer weather but instead sailed for Mexico, setting off an international chase by Sidney to recover his child.

At this moment in history, continuing an effort after the end of the revolution to lessen the influence of the Catholic Church, Mexican President Lazaro Cardenas was persecuting Catholics. The church set up safe houses to shelter those targeted and to provide places where certain rituals could take place. Stephens had arranged for Annette and Cherry to hide in one of these in the heart of Mexico City.

Pepper was furious, enraged, at his wife’s betrayal. He determined to use whatever means at his disposal to get his daughter, if not his wife, back. On May 13, 1936, headlines blazed on the front page of Mexico City’s El Universal, featuring photos of both Annette and Cherry, and naming Annette as a kidnapper. Pepper rushed to Mexico City and enlisted the help of the chief of police in his search.

Mexico has always been a male-dominated society and, even today, wives are often viewed as “property.” In the mid-1930s any man whose wife had cheated and, worse, tried to take his child from him, would have elicited anger and ferocious support on the part of local law enforcement. That Sidney Pepper was an influential lawyer who could make a lot of trouble through the US Embassy didn’t hurt his cause.

Annette and Cherry were located, probably reported by someone who saw their photos in the newspaper. Sidney and the chief descended with a vengeance on Annette and Louis’s hideout. As the story goes, arriving at the safe house the chief pounded on the door. When Annette opened it, the chief handed Sidney his pistol and instructed him to “Shoot the bitch!” Since the chief probably did not speak much English and Sidney probably did not speak Spanish, the exact wording is probably unreliable, but this is how Sidney would relate the story over and over again to Cherry as she was growing up.

Annette and Cherry spent the night in jail but were released the following morning and, amidst tears, shouts, and pleading, Sidney took his daughter back to the United States on the train. Cherry remembers only the train bathroom, with the train tracks racing beneath them when you lifted the toilet seat, and that she was afraid of falling in.

Annette lost custody of her daughter and would not see her for some time, but she would remain in Mexico for the next fifty years, forging a life and career as an artist and jewelry designer.

Although she led an active social life among those in the Mexican artist community, Annette Nancarrow, as she came to be known, was not a dilettante. She was a serious artist and designer; her paintings drew on the masculine energy of the mural era but incorporated a feminine sensibility that was all her own. They appeared in exhibitions and are in many private collections today. Her paintings are in the collections of the National Museum of American Women Painters in Washington, DC, where her name is inscribed in their wall, and at the Santa Fe Museum of Fine Art. Her jewelry—bold and innovative, and featuring pre-Columbian designs and figures—has been shown in collections at Bergdorf Goodman, Bendels, and Magnins in Los Angeles, and exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Photos of her jewelry appeared in Women’s Wear Daily and in Vogue, and her pieces have been purchased and worn by such women as Elizabeth Arden, Helena Rubenstein, Frida Kahlo, Anaïs Nin, Marion Anderson, Peggy Guggenheim, and many others.